By Tim Pelan

“It’s not pro-war or anti-war. It’s just the way things are,” Stanley Kubrick said of Full Metal Jacket, his 1987 adaptation of Gustav Hasford’s novel, The Short-Timers. Hasford was a combat correspondent with the Marine Corp in Vietnam, and Matthew Modine’s character Joker, who we follow through basic training and the battle of Hue during the 1968 Tet offensive, was shaped by his experiences. Kubrick signed up another ex-war correspondent, Michael Herr, the writer of the narration for Apocalypse Now to work with him on the script in what Herr wryly described as “one phone call lasting three years, with interruptions.” The point of the material to Kubrick was how the system breaks down and restructures young men into killing machines, as exemplified by R. Lee Ermey’s antonymously named Sergeant Hartman: “Your rifle is only a tool. It is a hard heart that kills.” Effectively, the film can be divided into two segments, harsh, brutalizing training in the first, and Vietnam in the second, although, strictly, the final segment, known as “The Sniper,” makes it three. Modine had recommended an old friend, Vincent D’Onofrio, for the role of gormless Leonard, aka Gomer Pyle (after the initial introduction, none of the marines are referred to by their actual names. The fact that they retain their nicknames or adopt new ones suggests a part of their old identity has been subsumed by the “lean, green, killing machine”). Pyle’s ineffectual inability to keep up has him singled out for particular attention and Joker is made to make him shape up. Ironically, Kubrick’s taskmaster approach fed resentment between the two actors. The one thing Pyle has going for him is he is an excellent marksman, which will have a tragic outcome. Once the others make it to Vietnam, Hartman has indoctrinated them so much that they can barely talk in little more than cliches of the “phony tough and the crazy brave,” sussing each other out in terms of point-scoring and domination. Joker tries to stay out of the shit by being assigned to the forces magazine Stars and Stripes, but the war comes for him anyway, and he will be forever changed by it.

Full Metal Jacket treats war phenomenologically, as Kubrick explained at the beginning of this piece. It just accepts wars as an unfortunate fact of human nature. Joker pisses off the brass by writing “Born to kill” on his helmet whilst wearing a peace badge on his uniform, expressing the “Jungian thing,” the duality of man. “Vietnam was such a phony war,” Kubrick told Alexander Walker, the Evening Standard critic, “in terms of the technocrats fine-tuning the facts like an ad agency, talking of ‘kill ratios’ and ‘hamlet pacification’ and inciting the men to falsify a ‘body count’ or at least total up the ‘blood trails’ on the assumption they’d lead to bodies somehow.” Joker comes up against this bullshit in his journalistic cushy number, cracking wise to his commander after the news of Tet, “Sir, does this mean Ann-Margret isn’t coming?” Jan Harlan, Kubrick’s brother in law, stated that Kubrick, without explaining it too broadly, wanted to suggest that everyone in the film wore a mask, to survive, to get through what war requires them to do. Nathan Abrams in his piece for Forward suggests that Full Metal Jacket could be Kubrick’s “stealth Holocaust movie” (famously, Kubrick pre-planned for so long on The Aryan Papers that he was beaten to the punch by Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List). In Hasford’s novel:

![]()

“Arguably,” Abrams writes, “Jewishness remained beneath the surface in two key characters. Joker (played by Mathew Modine) is a cerebral writer who’s smarter, more sensitive, streetwise and sympathetic than those around him. His spectacles denote his intelligence. He’s an insubordinate, wise-cracking smartass who clearly delights in showing how much cleverer he is than his superior officers. He’s also a mensch who helps the gormless Leonard ‘Gomer Pyle’ Lawrence (Vincent D’Onofrio) through his basic training. Joker can posture as only ‘phony tough.’ He feels real remorse at having to shoot a sniper, an act that he eventually performs as a mercy killing.

And by removing any suggestion that Pyle was the redneck of Hasford’s novel, Kubrick allows us the possibility of reading him as Jewish as well. Kubrick retained the name ‘Leonard,’ possibly because interwar Jewish parents, like his own, chose such regal-sounding names in trying to give their sons a boost toward upward mobility in America. Leonard was Kubrick’s own father’s middle name as well as the given name of the Jewish doctor Clam Fink in Norman Mailer’s 1967 novel Why Are We in Vietnam?”

D’Onofrio was asked by Kubrick to “Pyle” on 70 pounds to portray the character as a shy, flabby child-like innocent, out of his depth, the target of Hartman’s ire, a stain on his Corp. This equal opportunity bigot has it in for him. To further the Holocaust subtext further, Hartman berates him during PT to give him “One for the Kommandant.” The sergeant threatens to sterilize Pyle so that he “can’t contaminate the rest of the world.” And the blanket party beating, where his frustrated platoon take turns to beat him in his bunk across the stomach with bars of soap in towels? Holocaust survivors, upon arrival in Israel after the war, where disdainfully referred to as the Hebrew word for soap, sabon.

![]()

Hasford described the Parris Island training facility in Carolina as “symmetrical but sinister like a suburban death camp.” To double for this, Kubrick used the Territorial Army barracks in Enfield. Here, the camera slowly tracks around the room, following Hartman around the carefully regimented, symmetrical bunks, lockers, and recruits. For the sequence where he jogs them around their bunks, repeating “This is my rifle, this is my gun, this is for fighting, this (groin) is for fun” Kubrick was insistent they all were precise and uniform in their movements. “Guys”, he would say, “some of you are only jerking (your groin) twice. In time to the rhythm of the words, please.” The recruits are like insects, scuttling around the polished floor. Later, in Vietnam with green combat gear and hugging the blasted urban landscape, the transformation will be complete. As if they are cockroaches, the only survivors of the apocalypse around them.

Ermey was a former Marine Corp drill instructor who also served in Vietnam, He had initially settled in the Philippines after being medically discharged and acted as a technical advisor there on Apocalypse Now. Kubrick had envisioned him acting in the same role on FMJ but he had second thoughts when he saw Ermey tear into Territorial Army extras. His endlessly inventive invective cracked Kubrick up, and much of it found its way into the notoriously regimented director’s final script. “I’d say 50 percent of Lee’s dialogue, specifically insult stuff, came from Lee,” Kubrick admitted. However, with no acting background, Ermey had trouble remembering all his lines. Leon Vitali, Kubrick’s former actor turned dedicated assistant, had him drilled on videotape, hurling obscenities as he was pelted with oranges and tennis balls. The training sequence was shot after the combat at Beckton gas works in East London, standing in for the pummelled city of Hue. When Kubrick was dissatisfied with the hair clippers used to cut the recruits’ hair down to the scalp, Ermey called an old Marine buddy who revealed that at Parris Island they actually used clippers meant for shearing French poodles. The actor originally intended for the role of drill instructor, Tim Colceri, got compensated with the small but memorable role of helicopter door gunner, and a second unit trip to Norfolk flying over palm trees to boot.

Hartman has succeeded too well in training Pyle. We see him subsequent to the blanket party with a disturbing intensity to his face and voice—reciting the Credo in his bunk as he swears before God that he will kill his enemy. Pyle has Hartman in his sights. He has somehow squirreled away a full clip of live rounds, the eponymous “full metal jacket”. On their final night in hell, which they have seemingly passed through unscathed, his full volume drill instruction in the toilets has attracted Joker, on night watch, and the incongruously dressed Hartman in his smoky bear and shorts. “What in the name of Jesus H. Christ are you animals doing in my head?” he yells. Pyle is about to do for the animal in his head, by shooting Hartman, then turning the rifle on himself, obscenely sucking on the barrel to further hammer home the pornographic imagery of war that has been drilled into the recruits.

![]()

Jeff Westerman, “Animals In My Head”: “Hartman, when he realizes he’s going to have to put his life on the line to stop Pyle, smiles to himself in a strangely elated way, before he speaks his final sentences. He seems to be pleased, recognizing that Fate is allowing him a great moment in which to distinguish himself as a valorous Marine. And Pyle, too, smiles, at the same moment of realization—he has engaged his enemy head-on, and they are both now consciously stepping forward to play out their ultimate roles. It’s a smile of recognition which passes between them, rank against rank, life against life, authority versus individual will. One man will only give up his power by dying, and the other can only gain it through killing.”

For the shot of Pyle’s brains being blown against the white tiled wall behind him, Matthew Modine came up with the solution. He told Kubrick about William Friedkin’s To Live and Die In L.A., and the scene where William Petersen takes a shotgun blast to the face. They obtained a print and watched it slowed down with no sound. Rather than using a squib, which Kubrick’s crew had been attempting, they realized the solution here was someone flinging guts into the actors face with a catapult. Friedkin then spliced several frames to hide the effect coming from off camera. Kubrick used a three-foot long pipe, propelling a mixture of pasta and fake blood via pressurized air. At that speed, only one frame had to be removed. (Incidentally, it is extremely unlikely a recruit could sequester ammunition like this. The Marine Corp are fanatical about accounting for every round during training. Instead, real-life Parris Island veterans testify how they were intimidated on the best ways to commit suicide if they can’t cut it, told to open a vein with a razor blade lengthways down the arm.)

The shoot ran for thirty-nine weeks, over twice the estimated eighteen. Kubrick achieved the impossible, and made the abandoned Beckton gas works in East London stand in for the bombed city of Hue. He even shipped in two hundred palm trees from Spain, kept hydrated by the fire brigade. After the harrowing training segment, the sequences in Vietnam are full of grim humor until the agonizingly drawn out sniper sequence. Although Joker’s John Wayne act (“A day without sunshine is like a day without blood”) is shaken when the NVA attack his base during the night. In the novel, Joker and Rafterman, his photographer, hook up with his old pal Cowboy and the Lust Hog squad in a cinema, mocking John Wayne’s film, The Green Berets, full of “the phony tough and the crazy brave.” In the film, they meet in a courtyard, and Joker and Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin) square off as if they are overgrown schoolboys, albeit Lord of the Flies style—armed to the teeth, with no parental control. As Crazy Earl says, revealing his “friend”, a dead enemy soldier, “We’re jolly green giants, walkin’ the Earth, with guns!” Dig his smile of surprised delight later as he catches a second NVA soldier run across his sights in the ruins and lets rip with a burst, bringing him down, before Surfin’ Bird kicks in. The upbeat pop music a deliberate ironic counterpoint to the bizarre hellscape around them.

![]()

Bilge Ebiri: “I noted the bizarreness of the architecture of where Cowboy’s group was camped outside of Hue—specifically, the setting of the scene where Joker first meets them and they show them the dead Vietnamese lounging in a chair. The place seemed to be made up of circular entrances. I was in Vietnam last year and I tried to think if I had seen any architecture resembling this. Then it hit me—I saw this kind of architecture at one of the Imperial tombs, on the outskirts of—you guessed it—Hue, the ancient capital. It’s a wonderfully subtle move from someone who was working primarily from photographs.” Kubrick got ill-informed flack for filming in London, an ignorance born by clichéd views of Vietnam as primarily jungle and bamboo huts. In actual fact, the buildings closely resembled the basic architectural layout of the 20th century aspect of Hue—“all in this industrial functionalism style of the 1930s, with the square modular components and big square doors and square windows,” he recalled. Many of Beckton’s buildings had coincidentally been designed by the same French architect who had built in Hue. Production designer Anton Furst sent his team to the US Library of Congress to scour Vietnamese magazines. Adverts were microfilmed, blown up into signs and posters for Vietnamese verisimilitude. Kubrick secured three period-authentic M14 tanks from a sympathetic Belgian military (the US Army deferred). Six weeks of demolition work knocked off corners and blasted windows to resemble a war zone.

Kubrick’s precision applied as much to the seeming chaos of the Hue war scenes, his camera hugging the “blasted heath” as it prowls along with the crouching Marines. He once had the crew dig through solid concrete for one such shot. Gas heaters used to eliminate un-Vietnam like foggy breath caused breathing problems for the actors, out in the rubble for weeks on end, working on the same scene. “Beckton Gas Works on the Isle of Dogs was, besides Ground Zero during 9/11, the most toxic place I’ve ever had the displeasure of being,” Modine recalled. “We all knew we were crawling around in asbestos and we understood the dangers of that. But we had no understanding of the heinous chemicals that were in the soil. During tea breaks dust was always settling on the cakes and biscuits, floating on top of our tea. God knows how much we ingested and what effect it’s had on our bodies. When we got home and took our baths, the tubs would turn a cobalt blue from the dirt that was in our hair and on our bodies.”

Modine documented his time filming in what became known as the Full Metal Jacket Diary, now turned into an app. He also took many photographs on an old camera which Kubrick chided him about, knowing he was hoping to impress the former LOOK photographer. The Beckton set was surrounded by multi-colored cargo containers to obscure unwanted elements creeping into shot. “The containers are timeless and colorful,” Modine wrote. “Rusty red. Dull yellow. Orange. Plain steel. An efficient and inexpensive way to block out England.” The actor felt transported. “One corner has metamorphosed into a typical street in Da Nang. A beautiful pagoda is being constructed off in a field. In another corner is the destroyed city of Hue.”

![]()

Interviewed during a lull in fighting by a CBS news crew, the squad offer up their thoughts on the war. Joker lulls them with a seemingly cultured take on his enforced “tour”, straight from the book—“I wanted to meet interesting, stimulating people of an ancient culture, and kill them. I wanted to be the first kid on my block to get a confirmed kill.” The complexity of the location shoot and Kubrick’s perfectionism began to take a toll. “Days can’t be measured by the rise and set of the sun but only by the next call sheet,” wrote Modine. Kubrick was stuck on the ending, where a young female sniper has Eightball (Dorian Harewood) shot and used as bait to draw the squad out of cover, Adam Baldwin’s Animal Mother enraged and leading the charge across the square. Kubrick brought the actors into his motorhome. “You know, I’m not sure how I want to end this film. Do you guys have any ideas?”

There were already a couple of scrapped suggestions. Joker was to die, and his death would be intercut with clips of him as a young boy. The ending of the book was filmed, then discarded, with Animal Mother hacking off the sniper’s head and hoisting it aloft on the end of his weapon. Kubrick wanted the reveal of the sniper as a young girl to be shocking. As she begs for death’s release from her wounds, Joker reluctantly gets his interview wish, finishing her off. The final minutes of the film bring us full circle. The same eerie music plays over the sniper’s final moments as when Pyle shoots Hartman, and when Pyle receives the barrack-room blanket beating. Joker, upon delivering the coup de grace, is “born again hard” as he kids himself in voice over, reborn into a new world of shit, the valorous soldiers marching through the smoke and flame to the regressive marching rhythm of the Mickey Mouse Club song. Joker’s thousand-yard stare tells the true tale of how he feels though. As Modine put it, “It is the moment that Joker dies and has to spend the rest of his life alive.”

Tim Pelan was born in 1968, the year of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (possibly his favorite film), ‘Planet of the Apes,’ ‘The Night of the Living Dead’ and ‘Barbarella.’ That also made him the perfect age for when ‘Star Wars’ came out. Some would say this explains a lot. Read more »

![]()

“The more highly paid you were, or the closer to the actual shooting, the more enslaved you were likely to be. If you were right there on the set with film running, the pressure could be amazing, or so I was convincingly told by many of the cast and crew of Full Metal Jacket. I wasn’t the cameraman or the art director or even a grip, or, thank God, an actor. I was only even on the location two or three times, so maybe I wasn’t properly enslaved at all. I may have rewritten a few scenes 20 or 30 times—I would have done that anyway—but I never had to go through the number of takes Stanley would require. It was everything anyone ever said it was and more, and worse, whatever it took to ‘get it right,’ as he always called it. What he meant by that I couldn’t say, nor could hundreds of people who have worked for him, but none of us doubted that he knew what he meant.” —Michael Herr, Grove Press, 2000

Screenwriter must-read: Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr & Gustav Hasford’s screenplay for Full Metal Jacket [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

![Loader]() Loading...

Loading...

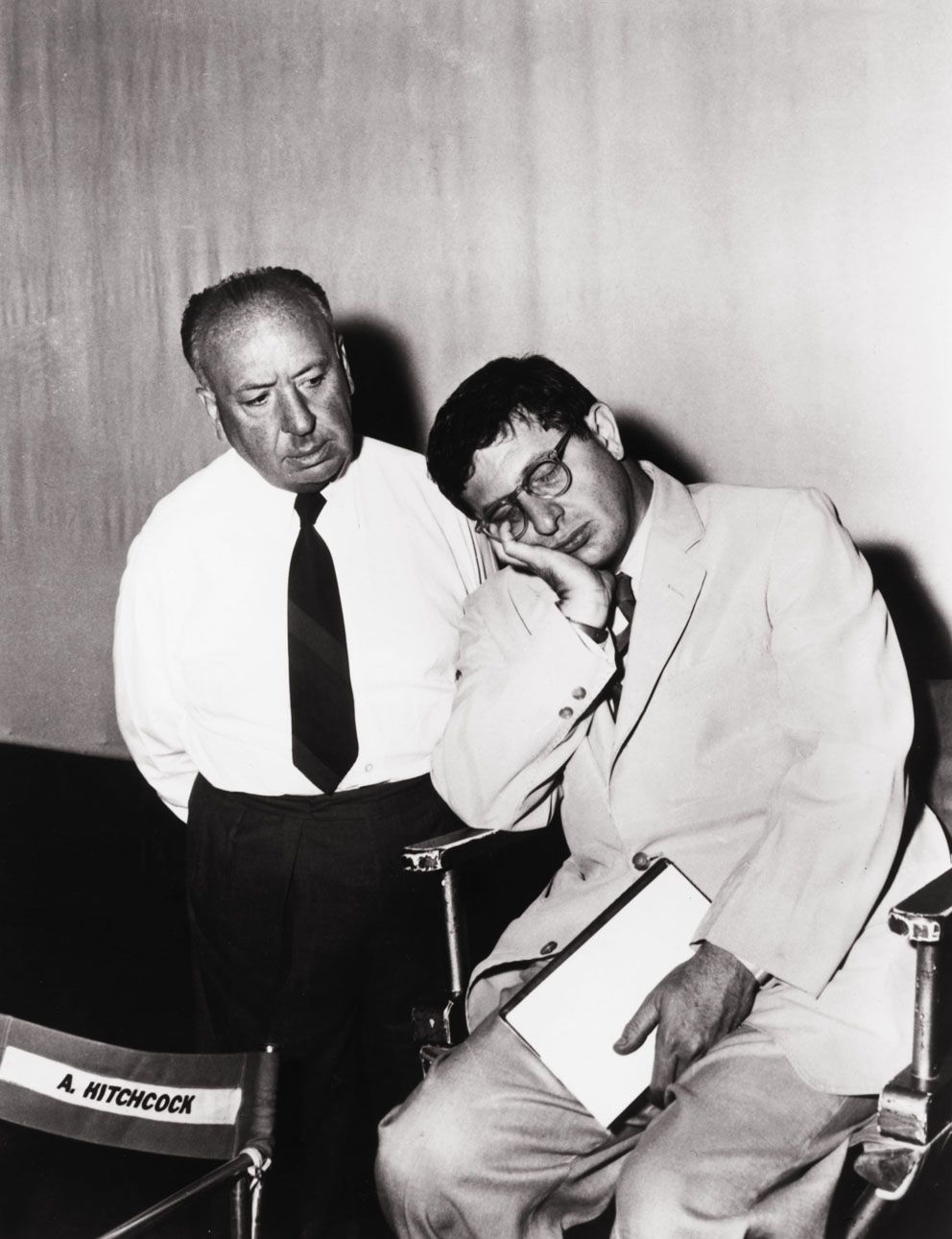

Having based his treatment on Gustav Hasford’s 1979 novel, The Short-Timers, Kubrick then met with Michael Herr—Vietnam war correspondent and author of Dispatches (1977)—to break the treatment down onto index cards, before Herr wrote the first draft of the screenplay. Michael Herr wrote the narration for Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), then co-wrote Full Metal Jacket (1987) with Stanley Kubrick, which contained elements of Dispatches. Kubrick, Herr, and Hasford would all receive a screenplay credit in the end. [Bonhams]

The cover of Kubrick’s draft of Full Metal Jacket and additional page of the script with Kubrick’s handwritten notes.

![]()

![]()

The Rolling Stone interview: Stanley Kubrick in 1987, by Tim Cahill. This article appeared in the August 27, 1987 issue of Rolling Stone.

He didn’t bustle into the room, and he didn’t wander in. Truth, as he would reiterate several times, is multi-faceted, and it would be fair to say that Stanley Kubrick entered the executive suite at Pinewood Studios, outside London, in a multifaceted manner. He was at once happy to have found the place after a twenty-minute search, apologetic about being late and apprehensive about the torture he might be about to endure. Stanley Kubrick, I had been told, hates interviews. It’s hard to know what to expect of the man if you’ve only seen his films. One senses in those films painstaking craftsmanship, a furious intellect at work, a single-minded devotion. His movies don’t lend themselves to easy analysis; this may account for the turgid nature of some of the books that have been written about his art. Take this example: “And while Kubrick feels strongly that the visual powers of film make ambiguity an inevitability as well as a virtue, he would not share Bazin’s mystical belief that the better film makers are those who sacrifice their personal perspectives to a ‘fleeting crystallization of a reality [of] whose environing presence one is ceaselessly aware.’”

One feels that an interview conducted on this level would be pretentious bullshit. Kubrick, however, seemed entirely unpretentious. He was wearing running shoes and an old corduroy jacket. There was an ink stain just below the pocket where some ball point pen had bled to death.

“What is this place?” Kubrick asked.

“It’s called the executive suite,” I said.

“I think they put big shots up here.”

Kubrick looked around at the dark wood-paneled walls, the chandeliers, the leather couches and chairs. “Is there a bathroom?” he asked, with some urgency.

“Across the hall,” I said.

![]()

The director excused himself and went looking for the facility. I reviewed my notes. Kubrick was born in the Bronx in 1928. He was an undistinguished student whose passions were tournament-level chess and photography. After graduation from Taft High School at the age of seventeen, he landed a prestigious job as a photographer for Look magazine, which he quit after four years in order to make his first film. Day of the Fight (1950) was a documentary about the middleweight boxer Walter Cartier. After a second documentary, Flying Padre (1951), Kubrick borrowed $10,000 from relatives to make Fear and Desire (1953), his first feature, an arty film that he now finds “embarrassing.” Kubrick, his first wife and two friends were the entire crew for the film. By necessity, Kubrick was director, cameraman, lighting engineer, makeup man, administrator, propman and unit chauffeur. Later in his career, he would take on some of these duties again, for reasons other than necessity.

Kubrick’s breakthrough film was Paths of Glory (1957). During the filming, he met an actress, Christiane Harlan, whom he eventually married. Christiane sings a song at the end of the film in a scene that, on four separate viewings, has brought tears to my eyes. Kubrick’s next film was Spartacus (1960), a work he finds disappointing. He was brought in to direct after the star, Kirk Douglas, had a falling-out with the original director, Anthony Mann. Kubrick was not given control of the script, which he felt was full of easy moralizing. He was used to making his own films his own way, and the experience chafed. He has never again relinquished control over any aspect of his films.

And he has taken some extraordinary and audacious chances with those works. The mere decision to film Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1961) was enough to send some censorious sorts into a spittle-spewing rage. Dr. Strangelove (1963), based on the novel Red Alert, was conceived as a tense thriller about the possibility of accidental nuclear war. As Kubrick worked on the script, however, he kept bumping up against the realization that the scenes he was writing were funny in the darkest possible way. It was a matter of slipping on a banana peel and annihilating the human race. Stanley Kubrick went with his gut feeling: he directed Dr. Strangelove as a black comedy. The film is routinely described as a masterpiece.

Most critics also use that word to describe the two features that followed, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1971). Some reviewers see a subtle falling off of quality in his Barry Lyndon (1975) and The Shining (1980), though there is a critical reevaluation of the two films in process. This seems to be typical of his critical reception. Kubrick moved to England in 1968. He lives outside of London with Christiane (now a successful painter), three golden retrievers and a mutt he found wandering forlornly along the road. He has three grown daughters. Some who know him say he can be “difficult” and “exacting.” He had agreed to meet and talk about his latest movie, Full Metal Jacket, a film about the Vietnam War that he produced and directed. He also co-wrote the screenplay with Michael Herr, the author of Dispatches, and Gustav Hasford, who wrote The Short-Timers, the novel on which the film is based. Full Metal Jacket is Kubrick’s first feature in seven years.

![]()

The difficult and exacting director returned from the bathroom looking a little perplexed. “I think you’re right,” he said. “I think this is a place where people stay. I looked around a little, opened a door, and there was this guy sitting on the edge of a bed.”

“Who was he?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he replied.

“What did he say?”

“Nothing. He just looked at me, and I left.”

There was a long silence while we pondered the inevitable ambiguity of reality, specifically in relation to some guy sitting on a bed across the hall. Then Stanley Kubrick began the interview:

I’m not going to be asked any conceptualizing questions, right?

All the books, most of the articles I read about you—it’s all conceptualizing.

Yeah, but not by me.

I thought I had to ask those kinds of questions.

No. Hell, no. That’s my… [He shudders.] It’s the thing I hate the worst.

Really? I’ve got all these questions written down in a form I thought you might require. They all sound like essay questions for the finals in a graduate philosophy seminar.

The truth is that I’ve always felt trapped and pinned down and harried by those questions.

![]()

Questions like [reading from notes] “Your first feature, Fear and Desire, in 1953, concerned a group of soldiers lost behind enemy lines In an unnamed war; Spartacus contained some battle scenes; Paths of Glory was an indictment of war and, more specifically, of the generals who wage it; and Dr. Strangelove was the blackest of comedies about accidental nuclear war. How does Full Metal Jacket complete your examination of the subject of war? Or does it?”

Those kinds of questions.

You feel the real question lurking behind all the verblage is “What does this new movie mean?”

Exactly. And that’s almost impossible to answer, especially when you’ve been so deeply inside the film for so long. Some people demand a five-line capsule summary. Something you’d read in a magazine. They want you to say, “This is the story of the duality of man and the duplicity of governments.” [A pretty good description of the subtext that informs Full Metal Jacket, actually.] I hear people try to do it—give the five-line summary—but if a film has any substance or subtlety, whatever you say is never complete, it’s usually wrong, and it’s necessarily simplistic: truth is too multifaceted to be contained in a five-line summary. If the work is good, what you say about it is usually irrelevant. I don’t know. Perhaps it’s vanity, this idea that the work is bigger than one’s capacity to describe it. Some people can do interviews. They’re very slick, and they neatly evade this hateful conceptualizing. Fellini is good; his interviews are very amusing. He just makes jokes and says preposterous things that you know he can’t possibly mean. I mean, I’m doing interviews to help the film, and I think they do help the film, so I can’t complain. But it isn’t… it’s… it’s difficult.

So let’s talk about the music in Full Metal Jacket. I was surprised by some of the choices, stuff like “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’,” by Nancy Sinatra. What does that song mean?

It was the music of the period. The Tet offensive was in ’68. Unless we were careless, none of the music is post-’68.

I’m not saying it’s anachronistic. It’s just that the music that occurs to me in that context is more, oh, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison.

The music really depended on the scene. We checked through Billboard’s list of Top 100 hits for each year from 1962 to 1968. We were looking for interesting material that played well with a scene. We tried a lot of songs. Sometimes the dynamic range of the music was too great, and we couldn’t work in dialogue. The music has to come up under speech at some point, and if all you hear is the bass, it’s not going to work in the context of the movie. Why? Don’t you like “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’”?

Of the music in the film, I’d have to say I’m more partial to Sam the Sham’s “Wooly Bully,” which is one of the great party records of all time. And “Surfin’ Bird.”

An amazing piece, isn’t it?

![]()

“Surfin’ Bird” comes in during the aftermath of a battle, as the marines are passing a medevac helicopter. The scene reminded me of Dr. Strangelove, where the plane is being refueled in midair with that long, suggestive tube, and the music in the background is “Try a Little Tenderness.” Or the cosmic waltz in 2001, where the spacecraft is slowly cartwheeling through space in time to “The Blue Danube.” And now you have the chopper and the “Bird.”

What I love about the music in that scene is that it suggests postcombat euphoria—which you see in the marine’s face when he fires at the men running out of the building: he misses the first four, waits a beat, then hits the next two. And that great look on his face, that look of euphoric pleasure, the pleasure one has read described in so many accounts of combat. So he’s got this look on his face, and suddenly the music starts and the tanks are rolling and the marines are mopping up. The choices weren’t arbitrary.

You seem to have skirted the issue of drugs in Full Metal Jacket.

It didn’t seem relevant. Undoubtedly, marines took drugs in Vietnam. But this drug thing, it seems to suggest that all marines were out of control, when in fact they weren’t. It’s a little thing, but check out the pictures taken during the battle of Hue: you see marines in fully fastened flak jackets. Well, people hated wearing them. They were heavy and hot, and sometimes people wore them but didn’t fasten them. Disciplined troops wore them, and they wore them fastened.

People always look at directors, and you in particular, in the context of a body of work. I couldn’t help but notice some resonance with Paths of Glory at the end of Full Metal Jacket: a woman surrounded by enemy soldiers, the odd, ambiguous gesture that ties these people together…

That resonance is an accident. The scene comes straight out of Gustav Hasford’s book.

So your purpose wasn’t to poke the viewer in the ribs, point out certain similarities…

Oh, God, no. I’m trying to be true to the material. You know, there’s another extraordinary accident. Cowboy is dying, and in the background there’s something that looks very much like the monolith in 2001. And it just happened to be there. The whole area of combat was one complete area—it actually exists. One of the things I tried to do was give you a sense of where you were, where everything else was. Which, in war movies, is something you frequently don’t get. The terrain of small-unit action is really the story of the action. And this is something we tried to make beautifully clear: there’s a low wall, there’s the building space. And once you get in there, everything is exactly where it actually was. No cutting away, no cheating. So it came down to where the sniper would be and where the marines were. When Cowboy is shot, they carry him around the corner—to the very most logical shelter. And there, in the background, was this thing, this monolith. I’m sure some people will think that there was some calculated reference to 2001, but honestly, it was just there.

You don’t think you’re going to get away with that, do you?

[Laughs] I know it’s an amazing coincidence.

![]()

Where were those scenes filmed?

We worked from still photographs of Hue in 1968. And we found an area that had the same 1930s functionalist architecture. Now, not every bit of it was right, but some of the buildings were absolute carbon copies of the outer industrial areas of Hue.

Where was it?

Here. Near London. It had been owned by British Gas, and it was scheduled to be demolished. So they allowed us to blow up the buildings. We had demolition guys in there for a week, laying charges. One Sunday, all the executives from British Gas brought their families down to watch us blow the place up. It was spectacular. Then we had a wrecking ball there for two months, with the art director telling the operator which hole to knock in which building.

Art direction with a wrecking ball.

I don’t think anybody’s ever had a set like that. It’s beyond any kind of economic possibility. To make that kind of three-dimensional rubble, you’d have to have everything done by plasterers, modeled, and you couldn’t build that if you spent $80 million and had five years to do it. You couldn’t duplicate, oh, all those twisted bits of reinforcement. And to make rubble, you’d have to go find some real rubble and copy it. It’s the only way. If you’re going to make a tree, for instance, you have to copy a real tree. No one can “make up” a tree, because every tree has an inherent logic in the way it branches. And I’ve discovered that no one can make up a rock. I found that out in Paths of Glory. We had to copy rocks, but every rock also has an inherent logic you’re not aware of until you see a fake rock. Every detail looks right, but something’s wrong. So we had real rubble. We brought in palm trees from Spain and a hundred thousand plastic tropical plants from Hong Kong. We did little things, details people don’t notice right away, that add to the illusion. All in all, a tremendous set dressing and rubble job.

How do you choose your material?

I read. I order books from the States. I literally go into bookstores, close my eyes and take things off the shelf. If I don’t like the book after a bit, I don’t finish it. But I like to be surprised.

Full Metal Jacket is based on Gustav Hasford’s book The Short-Timers.

It’s a very short, very beautifully and economically written book, which, like the film, leaves out all the mandatory scenes of character development: the scene where the guy talks about his father, who’s an alcoholic, his girlfriend—all that stuff that bogs down and seems so arbitrarily inserted into every war story. What I like about not writing original material—which I’m not even certain I could do—is that you have this tremendous advantage of reading something for the first time. You never have this experience again with the story. You have a reaction to it: it’s a kind of falling-in-love reaction. That’s the first thing. Then it becomes almost a matter of code breaking, of breaking the work down into a structure that is truthful, that doesn’t lose the ideas or the content or the feeling of the book. And fitting it all into the much more limited time frame of a movie. And as long as you possibly can, you retain your emotional attitude, whatever it was that made you fall in love in the first place. You judge a scene by asking yourself, “Am I still responding to what’s there?” The process is both analytical and emotional. You’re trying to balance calculating analysis against feeling. And it’s almost never a question of “What does this scene mean?” It’s “Is this truthful, or does something about it feel false?” It’s “Is this scene interesting? Will it make me feel the way I felt when I first fell in love with the material?” It’s an intuitive process, the way I imagine writing music is intuitive. It’s not a matter of structuring an argument.

![]()

You said something almost exactly the opposite once.

Did I?

Someone had asked you if there was any analogy between chess and filmmaking. You said that the process of making decisions was very analytical in both cases. You said that depending on intuition was a losing proposition.

I suspect I might have said that in another context. The part of the film that involves telling the story works pretty much the way I said. In the actual making of the movie, the chess analogy becomes more valid. It has to do with tournament chess, where you have a clock and you have to make a certain number of moves in a certain time. If you don’t, you forfeit, even if you’re a queen ahead. You’ll see a grandmaster, the guy has three minutes on the clock and ten moves left. And he’ll spend two minutes on one move, because he knows that if he doesn’t get that one right, the game will be lost. And then he makes the last nine moves in a minute. And he may have done the right thing. Well, in filmmaking, you always have decisions like that. You are always pitting time and resources against quality and ideas.

You have a reputation for having your finger on every aspect of each film you make, from inception right on down to the première and beyond. How is it that you’re allowed such an extraordinary amount of control over your films?

I’d like to think it’s because my films have a quality that holds up on second, third and fourth viewing. Realistically, it’s because my budgets are within reasonable limits and the films do well. The only one that did poorly from the studio’s point of view was Barry Lyndon. So, since my films don’t cost that much, I find a way to spend a little extra time in order to get the quality on the screen.

Full Metal Jacket seemed a long time in the making.

Well, we had a couple of severe accidents. The guy who plays the drill instructor, Lee Ermey, had an auto accident in the middle of shooting. It was about 1:00 in the morning, and his car skidded off the road. He broke all his ribs on one side, just tremendous injuries, and he probably would have died, except he was conscious and kept flashing his lights. A motorist stopped. It was in a place called Epping Forest, where the police are always finding bodies. Not the sort of place you get out of your car at 1:30 in the morning and go see why someone’s flashing their lights. Anyway, Lee was out for four and a half months.

He had actually been a marine drill instructor?

Parris Island.

![]()

How much of his part comes out of that experience?

I’d say fifty percent of Lee’s dialogue, specifically the insult stuff, came from Lee. You see, in the course of hiring the marine recruits, we interviewed hundreds of guys. We lined them all up and did an improvisation of the first meeting with the drill instructor. They didn’t know what he was going to say, and we could see how they reacted. Lee came up with, I don’t know, 150 pages of insults. Off the wall stuff: “I don’t like the name Lawrence. Lawrence is for faggots and sailors.” Aside from the insults, though, virtually every serious thing he says is basically true. When he says, “A rifle is only a tool, it’s a hard heart that kills,” you know it’s true. Unless you’re living in a world that doesn’t need fighting men, you can’t fault him. Except maybe for a certain lack of subtlety in his behavior. And I don’t think the United States Marine Corps is in the market for subtle drill instructors.

This is a different drill instructor than the one Lou Gosset played in An Officer and a Gentleman.

I think Lou Gosset’s performance was wonderful, but he had to do what he was given in the story. The film clearly wants to ingratiate itself with the audience. So many films do that. You show the drill instructor really has a heart of gold—the mandatory scene where he sits in his office, eyes swimming with pride about the boys and so forth. I suppose he actually is proud, but there’s a danger of falling into what amounts to so much sentimental bullshit.

So you distrust sentimentality.

I don’t mistrust sentiment and emotion, no. The question becomes, are you giving them something to make them a little happier, or are you putting in something that is inherently true to the material? Are people behaving the way we all really behave, or are they behaving the way we would like them to behave? I mean, the world is not as it’s presented in Frank Capra films. People love those films—which are beautifully made—but I wouldn’t describe them as a true picture of life. The questions are always, is it true? Is it interesting? To worry about those mandatory scenes that some people think make a picture is often just pandering to some conception of an audience. Some films try to outguess an audience. They try to ingratiate themselves, and it’s not something you really have to do. Certainly audiences have flocked to see films that are not essentially true, but I don’t think this prevents them from responding to the truth.

Books I’ve read on you seem to suggest that you consider editing the most important aspect of the filmmaker’s art.

There are three equal things: the writing, slogging through the actual shooting and the editing.

You’ve quoted Pudovkin to the effect that editing is the only original and unique art form in film.

I think so. Everything else comes from something else. Writing, of course, is writing, acting comes from the theater, and cinematography comes from photography. Editing is unique to film. You can see something from different points of view almost simultaneously, and it creates a new experience. Pudovkin gives an example: You see a guy hanging a picture on the wall. Suddenly you see his feet slip; you see the chair move; you see his hand go down and the picture fall off the wall. In that split second, a guy falls off a chair, and you see it in a way that you could not see it any other way except through editing. TV commercials have figured that out. Leave content out of it, and some of the most spectacular examples of film art are in the best TV commercials.

![]()

Give me an example.

The Michelob commercials. I’m a pro-football fan, and I have videotapes of the games sent over to me, commercials and all. Last year Michelob did a series, just impressions of people having a good time—

The big city at night…

And the editing, the photography, was some of the most brilliant work I’ve ever seen. Forget what they’re doing—selling beer—and it’s visual poetry. Incredible eight-frame cuts. And you realize that in thirty seconds they’ve created an impression of something rather complex. If you could ever tell a story, something with some content, using that kind of visual poetry, you could handle vastly more complex and subtle material.

People spend millions of dollars and months’ worth of work on those thirty seconds.

So it’s a bit impractical. And I suppose there’s really nothing that would substitute for the great dramatic moment, fully played out. Still, the stories we do on film are basically rooted in the theater. Even Woody Allen’s movies, which are wonderful, are very traditional in their structure. Did I get the year right on those Michelob ads?

I think so.

Because occasionally I’ll find myself watching a game from 1984.

It amazes me that you’re a pro-football fan.

Why?

It doesn’t fit my image of you.

Which is…

Stanley Kubrick is a monk, a man who lives for his work and virtually nothing else, certainly not pro football. And then there are those rumors…

I know what’s coming.

![]()

You want both barrels?

Fire.

Stanley Kubrick is a perfectionist. He is consumed by mindless anxiety over every aspect of every film he makes. Kubrick is a hermit, an expatriate, a neurotic who is terrified of automobiles and who won’t let his chauffeur drive more than thirty miles an hour.

Part of my problem is that I cannot dispel the myths that have somehow accumulated over the years. Somebody writes something, it’s completely off the wall, but it gets filed and repeated until everyone believes it. For instance, I’ve read that I wear a football helmet in the car.

You won’t let your driver go more than thirty miles an hour, and you wear a football helmet, just in case.

In fact, I don’t have a chauffeur. I drive a Porsche 928 S, and I sometimes drive it at eighty or ninety miles an hour on the motorway.

Your film editor says you still work on your old films. Isn’t that neurotic perfectionism?

I’ll tell you what he means. We discovered that the studio had lost the picture negative of Dr. Strangelove. And they also lost the magnetic master soundtrack. All the printing negatives were badly ripped dupes. The search went on for a year and a half. Finally, I had to try to reconstruct the picture from two not-too-good fine-grain positives, both of which were damaged already. If those fine-grains were ever torn, you could never make any more negatives.

Do you consider yourself an expatriate?

Because I direct films, I have to live in a major English-speaking production center. That narrows it down to three places: Los Angeles, New York and London. I like New York, but it’s inferior to London as a production center. Hollywood is best, but I don’t like living there. You read books or see films that depict people being corrupted by Hollywood, but it isn’t that. It’s this tremendous sense of insecurity. A lot of destructive competitiveness. In comparison, England seems very remote. I try to keep up, read the trade papers, but it’s good to get it on paper and not have to hear it every place you go. I think it’s good to just do the work and insulate yourself from that undercurrent of low-level malevolence.

I’ve heard rumors that you’ll do a hundred takes for one scene.

It happens when actors are unprepared. You cannot act without knowing dialogue. If actors have to think about the words, they can’t work on the emotion. So you end up doing thirty takes of something. And still you can see the concentration in their eyes; they don’t know their lines. So you just shoot it and shoot it and hope you can get something out of it in pieces. Now, if the actor is a nice guy, he goes home, he says, “Stanley’s such a perfectionist, he does a hundred takes on every scene.” So my thirty takes become a hundred. And I get this reputation. If I did a hundred takes on every scene, I’d never finish a film. Lee Ermey, for instance, would spend every spare second with the dialogue coach, and he always knew his lines. I suppose Lee averaged eight or nine takes. He sometimes did it in three. Because he was prepared.

![]()

There’s a rumor that you actually wanted to approve the theaters that show Full Metal Jacket. Isn’t that an example of mindless anxiety?

Some people are amazed that I worry about the theaters where the picture is being shown. They think that’s some form of demented anxiety. But Lucas-films has a Theater Alignment Program. They went around and checked a lot of theaters and published the results in a [1985] report that virtually confirms all your worst suspicions. For instance, within one day, fifty percent of the prints are scratched. Something is usually broken. The amplifiers are no good, and the sound is bad. The lights are uneven…

Is that why so many films I’ve seen lately seem too dark? Why you don’t really see people in the shadows when clearly the director wants you to see them?

Well, theaters try to put in a screen that’s larger than the light source they paid for. If you buy a 2000-watt projector, it may give you a decent picture twenty feet wide. And let’s say that theater makes the picture forty feet wide by putting it in a wider-angle projector. In fact, then you’re getting 200 percent less light. It’s an inverse law of squares. But they want a bigger picture, so it’s dark. Many exhibitors are terribly guilty of ignoring minimum standards of picture quality. For instance, you now have theaters where all the reels are run in one continuous string. And they never clean the aperture gate. You get one little piece of gritty dust in there, and every time the film runs, it gets bigger. After a couple of days, it starts to put a scratch on the film. The scratch goes from one end of the film to the other. You’ve seen it, I’m sure.

That thing you see, it looks like a hair dangling down from the top of the frame, sort of wiggling there through the whole film?

That’s one manifestation, yeah. The Lucas report found that after fifteen days, most films should be junked. [The report says that after seventeen days, most films are damaged.] Now, is it an unreal concern if I want to make sure that on the press shows or on key city openings, everything in the theater is going to run smoothly? You just send someone to check the place out three or four days ahead of time. Make sure nothing’s broken. It’s really only a phone call or two, pressuring some people to fix things. I mean, is this a legitimate concern, or is this mindless anxiety?

Initial reviews of most of your films are sometimes inexplicably hostile. Then there’s a reevaluation. Critics seem to like you better in retrospect.

That’s true. The first reviews of 2001 were insulting, let alone bad. An important Los Angeles critic faulted Paths of Glory because the actors didn’t speak with French accents. When Dr. Strangelove came out, a New York paper ran a review under the head Moscow could not buy more harm to America. Something like that. But critical opinion on my films has always been salvaged by what I would call subsequent critical opinion. Which is why I think audiences are more reliable than critics, at least initially. Audiences tend not to bring all that critical baggage with them to each film. And I really think that a few critics come to my films expecting to see the last film. They’re waiting to see something that never happens. I imagine it must be something like standing in the batter’s box waiting for a fast ball, and the pitcher throws a change-up. The batter swings and misses. He thinks, “Shit, he threw me the wrong pitch.” I think this accounts for some of the initial hostility.

Well, you don’t make it easy on viewers or critics. You’ve said you want an audience to react emotionally. You create strong feelings, but you won’t give us any easy answers.

That’s because I don’t have any easy answers.

![]()

Thanks to the great folks at Movie Geeks United!, Tim Cahill’s 1987 interview with Stanley Kubrick, published in Rolling Stone magazine, is now available in its taped entirety. Enjoy two hours with Kubrick discussing his latest film Full Metal Jacket. For more exclusive Kubrick-related audio materials, visit The Kubrick Series.

Kubrick’s casting note in his draft of the Full Metal Jacket script, courtesy of Will McCrabb.

![]()

Kubrick’s daughter Vivian—who appears uncredited as a news-camera operator at the mass grave—shadowed the filming of Full Metal Jacket and shot eighteen hours of behind-the-scenes footage for a potential ‘making-of’ documentary similar to her earlier film documentary on Kubrick’s The Shining; however, in this case, her work did not come to fruition. Snippets of her work can be seen in the 2008 documentary Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes.

Matthew Modine, star of Full Metal Jacket, has published a digital recreation of his limited edition (now out of print) book. Full Metal Jacket Diary iPad app includes over 400 high-res photos from the set, five chapters from Modine’s book, and a four-hour audio experience that takes you through the production, beginning to end.

A Pinewood Dialogue with Matthew Modine offers rare insight into Kubrick’s techniques in directing his actors.

DOUGLAS MILSOME BSC, ASC

Douglas Milsome BSC, ASC, who had pulled focus for John Alcott BSC on The Shining, stepped in as cinematographer for Stanley Kubrick on this film, which the director again opted to shoot with ARRIFLEX 35BL cameras. Despite being set in Vietnam, the entire film was produced and filmed in England—at Pinewood Studios, Bassingbourn Barracks and Beckton Gasworks. Milsome experimented with different shutter angles for battle scenes, a technique Janusz Kaminski borrowed for Saving Private Ryan.

September 1987 issue of American Cinematographer, detailing the making of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, by Ron Magid.

It has been exactly thirty years since Stanley Kubrick’s first “war movie” Paths Of Glory, laid the foundation for his undisputed status as a world class filmmaker. The film is at times naively ideological but full of power and passion in its belief that the common man is merely a pawn in the game of war. Now, on the thirtieth anniversary of Paths Of Glory, Kubrick has presented us with what is arguably his most cynically Produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick Director of Photography, Douglas Milsome despairing, grim and disturbing film ever: Full Metal Jacket. The common man may still be a pawn of the government’s war machine, but this time around the price of obedience isn’t his life—although that may become forfeit-but his humanity. The title refers to a type of bullet commonly used in the Vietnam war, but it might also reflect the icy documentary-like detachment that characterizes the film’s sardonic tone.

Kubrick is definitely a team player, so it comes as no surprise that the man he chose to shoot Full Metal Jacket, Douglas Milsome, has been a participant on every one of his films beginning with A Clockwork Orange, where he served as the late John Alcott’s focus puller. Milsome quickly moved up through the ranks, becoming Alcott’s first assistant on The Shining. lt was on this film that he was allowed to shoot some first unit footage after Alcott left to work on another project. On his own after fifteen years with Alcott, Milsome has proved himself a worthy successor to his great mentor, whose style and meticulous attention to detail he tries to emulate. “I’d like to carry on where John stopped, actually,” he says. “I thought he was a great photographer and I learned a lot from him working with Stanley. I use the Alcott System all the time now. He taught me how to use black and white Polaroids to measure a great deal more than just exposure—it gives you the balance and allows you to go much higher or lower than the meter would otherwise indicate against film speed. The Polaroid film delineates very well between light and shade, and also gives a tremendously good idea of how windows are going to look if they’re over- or-underlit. The passing of John was such a blow to me that I’ve determined to try to perpetuate what he was trying to do. He lit like no other cameraman, so effectively with little or no light. Most of his lighting went into one suitcase, and that’s what I like and it’s what Stanley likes too.”

Although Kubrick’s films take notoriously long to shoot, nothing is left to chance and much of that time is spent in pre-production with the cinematographer. “Although I was actually on the film for a year and a half,” Milsome points out, “the shooting actually took a lot less time than people believe. The actual shooting took just over six months and we had to shut down for some twenty plus weeks due to injuries and accidents. My period of pre-production, however, was considerably longer than most. There’s always an awful lot to discuss with Stanley during pre-production because there’s so much involved with his films. They’re always big subjects, so the cinematographer is often brought in quite a bit earlier than usual, not just to check the equipment but to check every single aspect of every possible situation to the nth degree. It involves painstaking time for discussion. He’s just as methodical in his prep as he is in his shooting. Sometimes his prep takes as long as his shooting, often longer. He gives a new meaning to the word meticulous’ and the word ‘methodical’. As far as the lighting is concerned, that’s open to discussion. We build models of our sets and discuss how to light them and then we do extensive testing.”

![]()

Nearly all of the equipment used by Milsome on Full Metal Jacket was owned by Kubrick, who maintains stores of the most up-to-date and advanced equipment available. For many of the large tracking shots that comprise much of the film’s action footage, a variety of cranes and Steadicam were employed. Primarily, Milsome used the Arri BL camera and Zeiss high speed lenses. For some extreme slow motion effects, Kubrick purchased two of Doug Fries’ high speed cameras adapted from standard Mitchells, which were used in combination with numerous Nikon lenses. From its inception, Kubrick and Milsome agreed that Full Metal Jacket should have the desaturated, grainy look of a documentary. “We did that by using the high speed Kodak 5294, which we rated at 800 ASA all the way through,” Milsome recalls. “It should’ve been 400, so we were pushing it a little beyond where it would’ve given us a really solid black. By pushing the film all the way, we were able to bring the fog level up, and there was a natural lean toward the milkier, less solid blacks and grays, which documentary film tends to have. The film helped us a lot in achieving that look, coupled with the fact that we were working wide open. Even on days where it was fairly hazy but sunny, we used a lot of neutral density filters on the camera purely as a means of reducing the light transmission through the lens, which took some of the contrast out of the image and flattened it a little more. Also, we shot without an 85 correction filter for daylight, which gave us an extra % of a stop in hand. We pulled the blue out to make it look less cold, but we were able to correct for this color shift on the set. It just enabled us to get that little extra half hour or hour’s shooting at the end of the day.”

That extra bit of time can be crucial. Though Kubrick’s films have lengthy schedules, it isn’t because he tends to work at a leisurely pace. Kubrick’s demanding perfectionism is both a strain and an extremely rewarding attitude for those used to working with directors who expect less, Milsome explains: “I’ve actually had a lot harder time working for a lot less talented people than Stanley. He’s a drain because he saps you dry, but he works damn hard himself and expects everybody else to. Sometimes it becomes a plod because it’s so slow and intricate, but he loves to do things quite differently than what’s ever been done before. You can’t really do that sort of thing off the top of your head, so you work very hard to get it together and make something different which bears his mark. That can be a little overbearing and it tends to zap you and take up nearly all of your time. Sometimes the relationship can get a little strained because you’ve got to be devoted to him. You eat, drink and sleep the movie, and you’re under contract to Stanley body and soul. But he allows you the time to get everything absolutely right, which is what I find so rewarding.”

It is this insistence on achieving perfection regardless of how many takes are necessary for which Kubrick is most infamous. “Stanley always has done many, many takes” Milsome says, “but in fact, the many takes are not just repetitions of the same thing, they are often building upon a theme or idea that can mature and develop into something quite extraordinary. The whole structure of the scene can actually change during the operation of filming it. Also, Stanley gets a lot more out of his actors after he works with them a lot longer. It’s especially valuable in bringing out something in actors who may not be exactly up to the part, but Stanley works on them jolly hard until they produce the goods. That’s why he’s so good with actors: in the end, he’ll rehearse and rehearse them until they’re word perfect, and when they’ve got the words perfect then the rest has to happen—they then have to act. The large number of takes are used mainly to get something out of the actors that they’re not willing to provide right away. Of course, it’s demanding on the crew as well, but it’s a lot harder for the actors than it is for us. Once you’ve done an eight or ten minute scene a number of times, after take thirty or thirty-five, you’re really into it!” Milsome laughs. “Actually, it doesn’t always go that many takes. There were occasions on Full Metal Jacket where we went a few more than twenty-five or thirty takes, but we usually didn’t average more than ten to fifteen takes, although sometimes we’d go back and reshoot certain scenes later.”

![]()

Full Metal Jacket was shot entirely in England on sets ranging from a meticulously reconstructed Marine Corps, barracks to a blasted coke plant that served as the background to the Tet Offensive at the end of the film. The two part structure of the film necessitated recreating the Marine training camp at Parris Island in great detail for the basic training of the “grunts” that comprises the film’s grueling first half, while the second half of the film had to look like Vietnam location footage. Surprisingly, Kubrick found the ideal location for both sets in three different locations in the Northeast London area, not more than thirty miles apart. Parris Island’s training camp was a real military base in Bassingbourne, the barracks were built at Enfield, and the vast rubble and blasted buildings of the Tet Offensive were to be found in an East London gasworks.

The film opens inside the practical barracks set Kubrick had constructed at Enfield, as Milsome’s camera dollies along with Gny, Sgt. Hartman, played by Lee Ermev, as he indoctrinates the new “grunts” into the harsh, contradictory realities of Marine Corp life. Ermey, who is not an actor—he was actually the film’s technical advisor and a real life drill instructor—went through the sequence again and again, as Kubrick coached him on the precise inflections and mannerisms he wanted. All told, there were twenty-five takes or so the first time around. Ermey suffered injury in a car accident during shooting, after which “he’d improved no end as an actor,” Milsome relates. “I think he polished up his part quite well, so we did that particular scene all again. It was well worth it because he was so much better.”

In order to accommodate Kubrick’s proposed 360° shot. Milsome had to place all of his lighting outside the set, where it streamed in like cold sunlight through the large windows on either side of the barracks. Milsome had become accustomed to the director’s need for total freedom on the set, and so emulated Alcott’s daytime interior look for the palaces of Barry Lyndon and the lobby of The Shilling’s Overlook Hotel. “You can’t restrict anything Stanley wants to do by having a light source which shouldn’t be in the shot in the way,” he confirms. “Stanley likes the total freedom of being able to go anywhere at any time, so we reproduced the look of sunlight streaming through the windows. The lighting was all totally outside—there were no lamps inside anywhere except for the warm white deluxe daylight flourescent tubes in the overhead strips which were featured as a source light anyhow. So we just let the sunlight bleed in through the windows, which gave us a very natural single source light with a very soft fill, roughly about 3:1 on the shadow side. For this effect, we used the Par 600 watt lamps—each light has six 100 watt bulbs on it. We put four of these lamps outside each of the seven window’s in the set, so we had 24,000 watts burning outside each window. We had them filtered through the Rosco plastic 216 fibre, which gave us a very nice soft warm look.

![]()

“We used a very old moviola dolly with pneumatic tires which we let down so they had only a minimal amount of air in them. Although the floor of the barracks set wasn’t that smooth, we were able to wheel the dolly about the floor because the fairly flat tires actually made the shot very smooth. “The Louma crane was a great tool to us,” he says. “We did a lot of low angle tracking shots that ended with the camera soaring up into the sky as the troops were drilled. We had a remote hot head rig we could operate from below so we didn’t have to actually sit on the crane. We also mounted our camera on a Tulip crane with a Skycam extension, so we could get our lens over thirty feet up. We were able to use both types of crane rigs to create some really interesting camera moves that enhanced the training sequences. With this equipment, when they went over the obstacle course, we could go up with them, so there were quite a lot of shots of them climbing ropes and over barriers and things where we just followed them up.

“Because we were using the Louma crane quite often, we decided to have the crane ready assembled on a track always,” Milstone continues. “Although the crane itself is not that heavy-about a thousand pounds—it does take some hours to put together. We got a sixty seat coach, left the cab as it was, sawed the coachwork off and made the rear end into a thirty foot long tracking platform on which we laid our rails. Our crane was always completely assembled on this tracking coach, so we could drive it into any position within minutes, secure it with hydraulic jacks and be ready to do our shot very quickly.”

The climax of the film’s boot camp segment is carefully orchestrated in two powerful and disturbing nighttime scenes in the barracks, where the harsh blue moonlight filtering in through the windows is in sharp contrast to Milsome’s warm pink daylight look. The first sequence consists of the ritual beating of Gomer Pyle by his fellow recruits after they are forced to do push-ups when Hartman discovers a donut in the overweight private’s trunk. The sequence is eerie and frightening, and Pyle’s pain and horror are well served by Milsome’s objective photography and stylized lighting.

![]()

“We wanted to introduce a strong moonlight effect, which I think worked and gave a weird feeling to it all. It’s similar to the blue light we used in the maze in The Shining. For this scene, we used an open Fresnel Brute, which gave us very sharp shadows, and four 10K HMIs, white flame without condensers so they also cast very long and definite shadows. The Brute was placed at one end, giving a much wider, brighter beam, and the other four windows were each lit by one of the 10K HMIs. We then put half blues over them to give us a kind of Hollywood moonlight glow. Again, all of our light came from outside, and we used polystyrene to bounce the light or we bounced light from a 1000 watt snooted Lowell off the ceiling just to reflect a little bit of white light into the shadow side. We had a key of F.2, so we probably had about .70 on the shadow side, which meant we were working at roughly a 4:1 ratio.”

That same combination of naturalism and stylization pays off handsomely in the gruesome max of the film’s first half, wherein Pyle goes quietly mad after becoming a full-fledged Marine killing machine. Eyes rolled back into his skull and glowing with a strange inner light, he turns his rifle—with its full metal jacket shells—first on an outraged Hartman and then on himself. “That scene was very powerful,” Milsome agrees. “D’Onofrio flashes what people are now referring to as the ‘Kubrick crazy stare’. Stanley has a stare like that which is very penetrating and frightens the hell out of you sometimes—I gather he’s able to inject that into his actors as well. The light in D’Onofrio’s eyes was achieved quite naturally: the bathroom was tiled out quite white, so there was a massive amount of light coming back off them onto his face, which helped. “Again, the lighting was fairly straightforward. We had the same configuration as in the barracks, except with 5Ks in this case, placed four flights up shooting down through the bathroom window and throwing patterns on the wall, and we introduced the blue element again. The action part of the sequence didn’t take as much time as getting a performance. The pattern of Pyle’s brain on the wall after he shoots himself didn’t take all that long to get right, and for Hartman’s death, Ermey just shot straight back—I think he’s been hit before, because he bounced back well!’

Fade to black. When the lights come back on, we’re on a surdit street somewhere in Vietnam, following close on the heels of a voluptuous Vietnamese hooker as she propositions a couple of our boys. This shot typifies the style of the remainder of the film, as Milsome’s roving camera prowls through one vast urban landscape after another. “We used the Louma crane to a large extent on our exteriors,” Milsome says. “We had no exterior light apart from daylight and we used that right up until the eleventh hour. There was no day for night at all. We shot night for night lit by these Wendy lights, which each hold about two hundred bulbs. When hoisted up over a hundred feet on a cherry picker, they can light an enormous area from over two hundred yards away. They each took about 1200 amps, and we could actually light an area of 400 square yards quite easily at a light level of T1.4.”

![]()

Milsome also made use of a rather unusual dolly for many of the battle sequences: a camera car with its engine removed. “Stanley bought a Citreon Mahari, which proved to be quite useful,” he recalls. “It’s a very good, soft suspended tracking car, on which we mounted two cameras. We ripped the engine out of this one and pushed it along—it was fairly easy to push—and we did a lot of our tracking shots with that. We used it on Barry Lyndon to do many of our tracking shots across fields. It worked much better than a dolly because, tracking that fast, a dolly would have meant an unsteady picture, and I don’t think a Chapman crane could’ve tracked that fast with stability on a non-metallic surface. The car had an extremely soft ride and we were able to push it quite fast. We often had about six people pushing, one steering and three or four cameramen.”

The Tet Offensive, which compromises the primary focus of Full Metal Jacket’s grim second half, began quite treacherously at dusk on a Vietnamese holiday, during which time both sides had agreed there would be no fighting. Kubrick decided to stage the first wave of the offensive outside an American army base, where soldiers are holed up behind sandbags in flimsy tents. This set, called “the hooches,” was built at Bassingbourne, across from the camp that doubled as Parris Island. Milsome remembers the inherent difficulties in photographing huge scale special effects for this sequence: Choreographing our camera movement was extremely important, otherwise we’d waste a lot of money on effects we wouldn’t catch on film if we’d missed our mark. It became a question of rehearsing a number of times to insure we got it right.”

The lighting source for the night for night sequence were four Wendy lights posted in different corners of the training camp, which greatly facilitated quick changes from one angle to another. “If we wanted to change the direction in which we were shooting,” Milsome explains, “we’d just save one lamp and switch another one on so we always had a moonlit backlight source illuminating the scene. Once the Wendy lights are in position, they’re a hell of a job to maneuver, especially on soft ground, so having four saved us a great deal of time we would have spent moving them about, which enabled us to get our night work done that much faster. The lamps, from over 250 yards away, were able to give us a fast 1.4 backlight on the 94 Kodak film. We’d shoot at F.2, which was about one stop under. It was quite enough, and the rest of our light we would fill using sheets of styrene. We black velveted the actual trucks and the jib arms the lights were on so you couldn’t see them if we panned across them.”

![]()

The last twenty minutes of Full Metal Jacket comprise Private Joker’s “dark night of the soul,” as he and his photographer, Rafterman, played by Kevin Major Howard, are caught in an ambush along with the platoon they’ve been assigned to cover. The platoon leader has been killed, so leadership now falls to one of Joker’s fellow “grunts” from boot camp. Cowboy (Arliss Howard), who is ill suited to the task of negotiating his way out of the deadly situation. The tension is evident as the recruits huddle in fear behind a blasted wall as buildings blaze hellishly around them. “The final ambush sequence was shot over several afternoons around the tow end of the day, when the exposure wedge was dropping away,” Milsome recalls. “It was a good time to do that because we were wide open so we got the maximum effect from the flames. If you underexpose them, you don’t get the maximum effect. This way, the flame looked so much brighter and had a glowing quality, which was helped by the fact that they were all shot around magic hour-dusk time. We carried on with our shooting from late afternoon as it turned into evening, before it actually became night, for days. We were working with fast film and fast lenses at 1.4 going way down until the exposure level just went.

“Although we had exposure from the sky,” he continues, “we still needed to throw some light on the actors’ faces. We mainly did that using kicker lights that glanced off their heads or gave us a ¾ backlight. We primarily used Lowells or Redheads from quite a distance away, spotted up so they had a very directional beam that wouldn’t spill anywhere else. We introduced flame red into the color of the lights too, to give them a warm glow.” Interestingly, the scene of the troops awaiting Cowboy’s decision is as formally framed as Kubrick’s handheld-style battle footage that follows, which Milsome finds remarkable; “Stanley’s composition is very stylized. The way he places people is just amazing. You’ll never find a Kubrick setup where the actors’ feet are cut off every shot is either from the waist up or full length. Every one of his movies has that look; very square, very level and symmetrical. Things are placed exactly right every time. I use that style a lot even when I’m not working with him because that’s the sort of thing that I like myself. The use of extreme wide angle lenses is distinctive, too, and allows us a great area in which to manipulate the action. We used a lot of wide angles to compose interesting shots, as well as a lot of very close angles on the same shots, and then Stanley would cut from one extreme to the other.”

For the intensely visceral battle sequence that ensues, in which members of the platoon are mercilessly, repeatedly wounded by a hidden Vietnamese sniper in a largely successful attempt to draw the other members of the company out into the open, Milsome employed a great deal of Steadicam shots following the Americans across the battlezone. For the bloody closeups of the massacre itself, in which two soldiers are literally blown to pieces, Kubrick utilized exteme slow motion to emphasize the pain and the horror. “We had two high speed Fries cameras going at five times speed as the soldiers were shot,” Milsome remembers. “We just tore them open with lots of squibs and ran our cameras at very high speed. We used Nikon lenses to a very large extent in this sequence, not only for their extremely sharp definition and clarity, but for their many varying focal lengths. The range of the focal lengths go from five mil every mil up to one- or two hundred. The long focus lenses go up to 1200mm, which we could double and make 2400mm. They’re slow, but with the fast p stock we still had the aperture we needed on location without losing any of the quality—they don’t look like regular telephoto lenses. I think they have the supreme edge for optimum definition throughout the whole focal range.”

![]()

Milsome’s clinical, detached photography of Full Metal Jacket’s visceral battle footage lends Kubrick’s film a distant, yet poignant quality, which the cinematographer was afraid might be lost when he used the finely honed Nikon lenses. “I was hoping that detached documentary look would come across, but I worried that those Nikon lenses tend to bit into so much that there’s almost nothing you don’t see, whereas in documentaries, you can’t always see everything,” Milsome says. “I wanted the camera to seem detached—that’s exactly what the idea was. I did that by making the subject come to me, rather than going to them. There’s an intermediate distance where lenses become very detached, although over a certain focal length you can get too close or too wide and become very integrated into the action. We were aiming for the middle distance where we could reach a focal length that would allow us to remain slightly more divorced from the action and still see it all.”

The surviving G.I.s ultimately confront the sniper inside one of the bombed out buildings, in what appears to be some sort of decimated temple. The sniper is at first unaware that her enemies have entered the stronghold, but as soon as their presence is detected, the killer of half the platoon whirls about madly to do battle with the rest. The film’s supreme shock moment—the revelation that the sniper is merely a teenage girl—is poetically served by Milsome’s unusual stroboscopic slow motion cinematography. “We used a take where she looks very strange as she turned around,” he says, “where the fires blazing in the room seem almost to eat into her face as they bleed in from the background. This wasn’t just achieved by slowing the film down. We actually put the shutter of the camera out of phase with the movement of the film, which created a slight vertical strobe. As she was moving up and down and turning around, the flames seem to be standing still, and when she moved into the flames, they didn’t move with her but seemed to bleed onto her face. The film is actually exposing as it’s moving, which is what gives it that strobe effect. Normally, the film stops when the shutter opens, which freezes the picture., but in this case, the film’s still moving while the shutter’s open. Only slightly out of sync—maybe 25%—but it’s enough to give the effect of light lasting that much longer in the shot.”

The resolution of Private Joker’s moral ambiguity—as symbolized by the “Peace” button and the “Born To Kill” moniker he paradoxically sports on his helmet—is evidenced when he kills the young girl who so ruthlessly attacked them. Afterwards, he and the remaining soldiers march through the blasted concrete and twisted metal, a truly hellish landscape of angry orange and red flame, and Milsome’s camera captures the film’s final action with eloquent simplicity. “We really seemed to be lighting that sequence with calor gas and napalm,” Milsome wrily points out. “The buildings the soldiers march past were lit with a tank filled with 3000 gallons of burning gas, and we had oil burning Dantes which created the big fires that glowed in the background. The calor burns very red-yellow and the Dantes burn with a black smoke combined with a lot of color. Together, they produced a strong red glow. We did the final shot with a Louma crane, but it wasn’t shot from a great height. Instead, we extended the Louma crane some twenty feet away from the track, and we actually used it to get closeups of our actors on the march without making them come to camera. We also used a Python crane and a straight dolly on this same track, which was a thousand feet or so in length. We had a Brute lamp aimed at our actors and tracking with the camera from a long way off-fifty or sixty feet from the lens.”